Joaquin Miller (1837-1913)

By Walt Curtis © 1995

Did Oregon's first true laureates, Joaquin Miller, "the Poet of the Sierras," and Samuel Leonidas Simpson, "Oregon's sweetest singer," ever meet? It seems doubtful. If they didn't, it seems too bad. They had a lot in common. Both were lawyers, although neither practiced much law. Miller would hang out his shingle in Oro Fino, Idaho, but have to turn to pony express. A few years later in Canyon City, another gold rush town, he was elected judge.

Cincinnatus Hiner Miller was born, as the poet himself states in his California Diary, "in the year of our Lord 1837 on the 8th day of September" in Union County, Indiana. In later accounts he moved this date up to 1842, and transubstantiated his middle name into Heine, the great German poet. The Miller family came by wagon train to Eugene City in 1852. This Oregon youth was a nobody with an overweening ambition. Young "Nat" and a friend rolled a rock down a cliff, injuring a neighbor's cow. This impelled the two friends to head out prospecting for gold behind Mt. Shasta. From 1853 to 1860, Joaquin panned little gold, but fought against the Indians, taking an arrow through the jaw. He became a horse thief and then Indian lover (fathering a child -- Cali-Shasta), was incarcerated several times, and nearly hanged. He was befriended by outlaws. These years gave him material for his prose masterpiece Life Amongst the Modocs: Unwritten History (1873). The book would make him famous in England during the Captain Jack-led Modoc uprising, and make Mark Twain and Bret Harte envious. Enough so that they called him a liar.

Sorting out truth from fiction in Miller's life

is like -- perhaps unraveling a horse-hair lariat and weaving it back

together blindfolded. Will that rope hold when you lasso the mustang?

One of the most celebrated literary figures of the 19th century,

Joaquin taught Buffalo Bill how to dress! Poet and critic William

Everson [Brother Antoninus] hails Miller as the inceptor of the western

literary archetype. When he began publishing in Oregon, he couldn't

write for sour owl manure. He's still a mediocre poet whose reputation

has spiraled downward, to the bottom of the canon.

Sorting out truth from fiction in Miller's life

is like -- perhaps unraveling a horse-hair lariat and weaving it back

together blindfolded. Will that rope hold when you lasso the mustang?

One of the most celebrated literary figures of the 19th century,

Joaquin taught Buffalo Bill how to dress! Poet and critic William

Everson [Brother Antoninus] hails Miller as the inceptor of the western

literary archetype. When he began publishing in Oregon, he couldn't

write for sour owl manure. He's still a mediocre poet whose reputation

has spiraled downward, to the bottom of the canon.

Why do some of us love him? He's a cosmic character and the consumate showman...the splendid poseur who wrote authentic, noble and beautiful tales of our American West. Some of these stories he really lived. Alan Rosenus of Urion Press republished The Selected Writings of Joaquin Miller. The best evoke Oregon: "In the Land of Clouds" (Mt. Hood), "An Old Oregonian in the Snow" (Did Miller observe Joe Meek facing off the Californians? It's believable.). "Bill Cross and His Pet Bear," set in the Willamette Valley, is one of the True Bear Stories (1900), a fun collection from Capra Press.

Was Miller, as frequently accused, a fraud? No, not exactly. A close friend rose to his defense: "Joaquin Miller tells the truth as he sees it." Ambrose Bierce, who elsewhere called Miller "the greatest-hearted man I ever knew" stated that he was "the greatest liar this country ever produced. He cannot, or will not, tell the truth." Miller's response: "I always wondered why God made Bierce." M.M. Marberry published the most amazing expos© of Miller's fabrications in 1953. Splendid Poseur is such a fascinating and hilarious biography that it only amplifies one's admiration for the poet. Alan Rosenus feels Marberry is guilty of numerous deceits himself.

O.W. Frost, a Twayne biographer, gives us the most factual and authoritative information on Miller, even better than his own writings. He cross-checks legend with fact, elucidating names, dates and locations. In 1860, after stealing a horse and shooting a lawman, Hiner went up to Idaho. He rode pony express for his partner Isaac Mossman until Wells Fargo bought out the business in 1862. He then returned to Eugene City, and invested his profits in the Democratic Register. Noltner, the publisher, supported the Confederate or secessionist cause in Oregon. He made Joaquin the editor. It's a little bizarre, because his brother John served under Grant.

While publishing poetry, Joaquin railed against "Federal spies" and censorship. "The wild tide of affairs forbid silence...now plunging [America] into a vortex of oblivion...day by day becoming an enslaved nation." The Republicans in the state called him a traitor. Finally, in October of 1862, the U.S. Post Office denied mailing privileges to the weekly. (Years later Howard McKinley Corning would aggrandize the fiasco in "Joaquin Miller Crosses the Mountains.") Through his editorship, he corresponded with "Minnie Myrtle" -- Theresa Dyer, "poetess of the Coquelle" -- and went to Cape Blanco, wooed and won her hand in matrimony. He drove off another suitor at gunpoint, all within a week.

After failing to secure a paying literary career in San Francisco, the newlyweds returned to Eugene City. Soon Joaquin headed east of the Cascades with wife and baby to Canyon City, where a new gold strike was in progress. Thousands of miners gathered in a tent town called Whiskey Flat. Twenty-five million dollars in gold would be mined in and near Canyon Creek. C.H. Miller took his law books from saddle bags and tacked up a shingle. Recognized by miners from the California camps, he apologized to Bill Hurst, a notorious gunman, and paid him for the horse he'd stolen. Miller's exploits, boasts, buckskin clothing and six-shooters made him a natural to lead an expedition against hostile Indians.

The posse followed the natives from tracks of stolen horses and cattle, all the way to Harney County's Nevada border. Ambushed, two men were shot down at Joaquin's side. His bravado, and his "Secesh" leanings, no doubt helped get him elected to a Democratic judgeship in 1866. While there, from 1864-'70, he mainly wrote poetry, and maintained an extensive literary library. Minnie said he had a curious way of greeting visitors, heating up the stove to drive away the guest, and then, left alone, opening the window to go back to writing. When he read his poetry out loud in the saloons, curiously called "doggeries," some said he was "cracked." He possessed a "hair-trigger temper." To get back at Canyon Cityites, he penned a series of letters for a newspaper in The Dalles, under the rubric "Canyon City Pickles." Minnie thought them vulgar and "a disgrace."

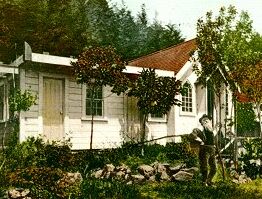

Joaquin Miller with wife (left) and daughter, 1912

Controversy surrounds Minnie and Joaquin's

marriage, falling out, and subsequent divorce. Abigail Scott Duniway

encouraged her to lecture on "The Poet and The Man," feeling Mrs.

Miller was abused. She was happy at first, but got bored. Rosenus

believes neither was suited for marriage vows. As a poet gentleman,

Miller never answered her charges against him. He nursed her in the

last years of her life, and wrote romantically about their life in

Canyon City. The cabin they shared is now an historical shrine. Minnie

lectured: "The cabin he built was a marvel to the camp. He built this

fence to keep the chickens out...planted fruit trees -- apple, pear,

plum or cherry. A pretty little stream gurgled through the yard, and

fell in gentle echoes down the sloping hill below."

Specimens (1868) and Joaquin et al (1869) were composed there, as was a first draft of Unwritten History. The poetry was panned, and when Miller ran for the Oregon Supreme Court, Minnie filed divorce papers. It was said that his wife was partying with circus men in Eugene, shacking up with a man named Hill at the Renfrew Hotel. It was the last straw, ending his legal/political career.

Changing the entire course of his life, the existentialist poet booked passage to San Francisco and then went on to Scotland. The beautiful green-eyed poetess Ina Coolbrith would help him pick laurel leaves in Sausalito to adorn the graves of the great ones -- Burns and Byron -- in England. Miller said to hell with Oregon and "sailed on" to world-wide fame, just like his persistent, unstoppable hero, Christopher Columbus.

Joaquin Miller "Poet of the Sierras"

At "The Hights" near Oakland, California Walt

Whitman, Oscar Wilde, Lily Langtry, the English literati, the Bierce

brothers, Mark Twain, Bret Harte and yes even his critics recognized

his "genius." What was it? His greatest achievement may well have been

the manufacture of his own career. A failed lawyer and ex-Oregonian

dressed in a buffalo robe, with bowie knife and pistols, in red

frontier shirt and boots and he wowed the British critics. Forever

after, Hiner Miller would be named "the Poet of the Sierras." He called

himself "the Byron of the Rockies." When in his old age he retired to

75 acres above Oakland and planted trees, he was a rich man. He

established Arbor Day in California. "I am afraid of the man who does

not love beauty," Miller wrote. "When I die I want to fall prostrate

like the giant Sequoia which I loved." Tourists would come from all

over the U.S. to watch him whittle on a goose quill, his writing

instrument of choice.

When introduced as California's greatest poet, Joaquin resentfully replied: "That title belongs to Bret Harte. I do not represent California, but a little hill called The Earth." Did he go a little bit wacko up there on "The Hights" above Oakland? Wasn't he a bit of a Dadaist? Receiving the Bay Area Womens' Press Club, he dressed in a wildcat skin; another time he recited "Mary Had a Little Lamb" to local savants, calling it "ideal" poetry. Jack London, Charles Warren Stoddard, Frank Norris, Edwin Markham (another son of Oregon) the Bierce boys -- all the Bay Area writers -- enjoyed his hospitality. "I'm deeply religious when I'm drunk," he admitted to sonneteer Sterling, "and when by accident I am deeply religious without being drunk, it's a sign I need a drink."

Miller came north at the time of the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition, posing in buckskin and boots for Fred Lockley, the Oregon Journal chronicler. In his essay "The New and the Old," Joaquin compares the speculators of the day with the honest old pioneers. The oldtimers who minted Oregon Beaver coins, on their return from the Gold Rush of 1848. Oregon farmers made more money than most prospectors, selling apples, wheat, produce and lumber to the '49ers. Our state's early prosperity came from gold fever, young Hiner's inspiration. The mature poet mocks "the new money-getting strangers." A greedy developer begged him to promote Stump Town's future. Miller recounts the damp and dismal figure's words:

"Can't you put this city into poetry? Yes, you kin. What's poetry good for, if it can't rize the price of land? Yes, an' tell 'em the old men never die; but jist git kivered with moss and blow away. Tell 'em that the timber grows so tall that it takes a man an' two small boys to see to the top of the trees! Yes, the biggest country, richest country and dogondest healthiest country this side of Jericho! Yes, it is."

Staring at him with contempt, as water slops and drips over his face, the poet comments about this "mossy, mouldy town of Portland," where "Mother Nature comes to the aid of the inhabitants and makes them web-footed, like the water-fowl." Miller himself was always a booster, a self-promoter. He lived in no less than 3 log cabins, in Canyon City, Washington D.C., and at "The Hights," where he died in 1913.

We Oregonians must reclaim that Oregon lad who tripped around behind Mt. Shasta. There he kept an amazing diary of literary dreams, chutzpah, and sexual innuendo, his California Diary. His sister-in-law sent it to Ina Coolbrith -- to burn it or not? Fortunately, she saved it!

The best of Joaquin Miller's sketches and memoirs go back to his fresh and rambunctious formative years in Oregon. Let's never forget our 19th century Webfoot bard who named himself after a Mexican bandido, Joaquin Murietta. He had enough public relations sense to claim friendship with a Modoc warrior. Long before Wounded Knee and the Nez Perc© war, this Oregon man passionately argued for a preserve for Native Americans, wherein they could roam free and unmolested in a primal Eden. We know instead the genocide of American history. Miller was the first to point out the shame, horror, bloodshed, and injustice of white dealings with native peoples. Unwritten History ought to be required reading for every schoolkid, just as Huckleberry Finn is today, where it isn't banned!

Selected Bibliography, Joaquin Miller

- Specimens, Carter Hines, Portland, 1868

- Joaquin et al

, S.J. McCormick, Portland, 1869

- Pacific Poems

, Whittingham and Wilkins, London, 1871

- Songs of the Sierras,

Longman, Green, Reader and Dyer, London; Roberts Bros., Boston, 1871

- Life Amongst the Modocs: Unwritten History

, London, 1873; Heyday Books/Urion Press, Berkeley,

1996 (Miller's autobiographical novel of mining and living with Indians behind Mt. Shasta)

-

Memorie and Rime, Funk & Wagnals, New York, 1884

- True Bear Stories

, Rand McNally & Co., New York, 1900; Binfords & Mort, Portland, 1949; Capra Press,

Santa Barbara, 1987 (forward by William Everson)

- Overland in a Covered Wagon: An Autobiography

, ed. Sidney G. Firman, D. Appleton, New York, 1930

- A Royal Highway of the World

, Metropolitan Press, Portland, 1932 (Miller's 1864 diary of Canyon City,

edited by Oregon's great bookman Alfred Powers)

- Joaquin Miller: His California Diary

, ed. John S. Richards, Dogwood Press, San Francisco, 1936

- Selected Writings of Joaquin Miller , Urion Press, Eugene, 1977; Saratoga, California, later editions

Secondary Sources on Miller

- American Literary Readings, Leonidas Warren Payne, Jr., Rand McNally & Co. , New York, 1917, pp 499-506

- Joaquin Miller Newsletter

, Margaret Guilford-Kardell, Blaine, Washington (an ongoing series on Miller.

- She's at 360 332 4411 or joaquin miller@juno.com)

History of Oregon Literature, Alfred Powers, Metropolitan Press, Portland, 1935 (big section on Minnie

vs. Joaquin controversy)

- Joaquin Miller, O.W. Frost, Twayne Publishers, Inc., New York, 1967 (authoritative biography)

Joaquin Miller and His Other Self, Harr Wagner, San Francisco, 1929

- The Mountain in the Sky, Howard McKinley Corning, Metropolitan Press, Portland, 1930, pp 19-23

- New American Legends, Lawrence Pratt, Wings Press, Mill Valley, 1958, "Joaquin Miller's Ride," pp 50-56

- Oregon History and Early Literature, John B. Horner, J.K. Gill Co., Portland, 1919, pp 424-433

- Oregon Literature, John B. Horner, Statesman Job Print, Salem/Corvallis, 1899, pp 35-48

- Splendid Poseur, M.M. Marberry, Thomas Crowell, 1953 (fascinating debunking biography)