Martina Gangle Curl (1906-1994): Peoples Art and the Mothering of Humanity David A. Horowitz, PhD© 2004

|

|||||

|

A muralist, painter, sketch artist, engraver, and block printer, Martina Gangle Curl fused her prolific art with a life-long devotion to the cause of labor and social justice. She was born on December 21, 1906 near Woodland, Washington into a poor Roman Catholic family of Austrian and Swedish background. One of seven children, Martina attended a country grade school and worked with her mother as a migrant fruit picker. I was optimistic and liked people, animals, trees, and farm work, she once recalled. Martina loved living close to nature, often going barefoot and dressing in overalls without a shirt. In the spring, she remembered, I looked for the first blooms of trilliums, Johnny-jump-ups, lady slippers, spring beauties, and roses. |

||||

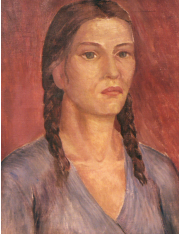

Martina Gangle Curl Self Portrait (oil on canvas) |

|||||

I was what would be considered a very poor Earth person raised in poverty, Martina recollected. Yet she noted that her mother was real smart and fed us kids oatmeal mush, milk when our cow was fresh, eggs, and a chicken two or three times a year, what vegetables we grew, and bread when she had flour. At the age of eight, however, Martina stopped including meat in her meals. I couldnt eat my rabbit and chicken friends or the cows when they had to be butchered, she reminisced with some humor.In 1917 Martinas father disappeared for fifteen months, most likely in search of a job. During this period Mrs. Gangle survived as a domestic washing clothes, sewing, or doing farm chores. Her mother told her about the trials and tribulations of life, Martina recalled, but she was honest, kind, and strong full of love especially for the underdog, for those who work hard and give and give and take little. Martinas sister Tillie once revealed that their mother often confessed that she would have ended it all if it had not been for her religion. I dont know anything about politics as I never had an education, Tillie remembered her mother saying time and time again, but I do know that all the problems of the world would be solved if only people would be kind to one another like Jesus told us to be.

|

|||||

|

Finding

herself among chattering young women in the art school locker room,

Martina kept her own counsel. I couldnt manage to get my brain to

function as to what I should say, she recalled in a subsequent

notebook entry. Their clothes, their conversation, and the things they

talked about were quite a contrast to mine. I did not feel at ease

around them. I found it hard to think of what to say so I said very

little just what was necessary. |

||||

With some bitterness, Martina remembered her classmates as well-dressed, protected, able to say the right words to smile when one is supposed to smile; to shake hands when one is supposed to shake hands; always able to say the right words at the right time. Despite the intimidating atmosphere of the Museum Art School, Martina benefited immensely from the influence of legendary painter and teacher, Harry Wentz. Having joined the faculty one year after the Art Schools doors opened in 1909, Wentz helped to promote a democratic ideal of art. He encouraged students to look inside themselves and paint what was real to them in their environment. To accomplish this Wentz advocated an intuitive approach once principles of color and design were mastered. The effect was to promote development of a Pacific Northwest regional style with an emphasis on local subject matter. Wentzs lessons had an enormous impact on the young Martina Gangle. When I started art school, she later recorded in her notebook in her idiosyncratic style, I had been doing my own drawings that I wanted to look like the people I saw around me. I didnt think about design. She soon began to realize that I had had instilled in me a certain kind of art that Id seen in advertisements and covers of the magazines I had read. When her work was called sweet she recalled feeling like disappearing thru the floor. Yet she took the assessment to heart and started to understand that she learned more from criticism than praise. I was beginning to realize the space between what was taught in Hi School, what [mother] told me, and the art school teaching, she remembered. Between 1932 and 1933 Martina exhibited oil portrayals of gardens, trees, and her son, as well as a watercolor of cherry pickers at the Portland Art Museum. Despite the disapproval of one of her instructors, her greatest love was drawing small flowers, a product of nostalgic memories of childhood. During summer vacations Martina supported her son and herself by picking fruit, a task that consumed ten-to-twelve hour days from daylight to dusk. In the summer of 1932 her son contracted diarrhea and a high fever. Life was not working as she had believed it would, she recorded in a third-person notebook observation. A fictional entry entitled Dreams of a Cherry Orchard contained the following passages: |

|||||

| I woke up one morning with a happy feeling. I had dreamed of being on a flying carpet with a beautiful gentleman. We held hands and reached out to the birds we past. The birds smiled at us; our carpet flew with them. They were all around us happy birds happy us. I dreamed a beautiful horse approached me and stopped. He said get on. Ive been sent to take you to a place. I got on. The horse, after a long, resting ride, stopped at the door of a palace. I went in. There stood a young prince who directed me to a beautiful bathroom. The tub was filled with warm water and ...was sweet-smelling.... | |||||

|

As Martina became increasingly aware of the enormous social class differences between more affluent classmates and herself, Harry Wentz came to the rescue. First, he helped the struggling student win a two-year scholarship to complete her training. Wentz also intervened to get Martina on the federal governments Public Works of Art program. | ||||

| Briefly run under the Treasury Department as a component of Franklin D. Roosevelts plan to initiate recovery from the Great Depression, the New Deals first public art project supported artists by paying them by the painting. During 1934 the PWA compensated Gangle $25 for each of three decorative oil panels. The first, entitled Farm Scene, Woman Feeding Chickens, was a portrait of her mother that found its way into a spring exhibit at the museum. The second painting depicted road laborers near her sister Tillies house on the Washington side of the Columbia River. The third, Prune Pickers, celebrated the beauty of everyday labor, prompting the Oregonian newspaper to compare it to the work of French realist, Jean-Franco Millet. | |||||

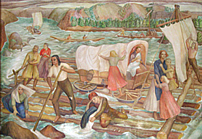

Despite these successes, Martina was physically exhausted by her fourth year of art school. After a full day of classes she was up most nights injecting her employers asthmatic husband with adrenalin shots. To raise extra money for her meager budget Gangle drew Wobbly (Industrial Workers of the World the radical trade union) Christmas cards to sell to classmates. But as the countrys economic catastrophe continued through 1935, she realized the impossibility of her dream of using art to earn enough to support her mother, son, and herself. I had a depression all my life, Martina once reminisced, so I didnt know that there was one until about the middle of the thirties. By then the young artist of twenty-nine felt ill-prepared for the work that was expected of me. With no prospects for a decent job, she anguished that she was poorer than when she started art school. Martina often recalled that during the Depression her beloved mother in rural Tualatin lived in a shack with rugs to keep the cold out instead of windows. Gangles etchings, linocuts, and lithographs of the mid-thirties often portrayed women and children fruit harvesters and other working people. She once speculated how different things would have been if she had gone directly to art school from high school. I would have had seven or eight years of ignorance of what was happening in the country, she reflected. I would no doubt have painted flowers and landscapes instead of poor families and people running from violence, homeless people sleeping on benches, etc. These images, which grew out of life experiences since childhood, saturated Martinas mind to the point of obsession. Her art mentors, she once mused, didnt realize what life had already done to my thinking. Until she read a series of Saturday Evening Post articles in 1931 criticizing the Soviet Union, Martina had no idea that a socialist country existed. Four years later she experienced another epiphany. At the end of the three-mile walk from her employers house in Southeast Portland to the Museum Art School, she came across a demonstration demanding a retrial for Tom Mooney, a San Francisco labor activist serving a long prison sentence after a controversial conviction for setting off a bomb in a pre-World War I preparedness parade. Martina remembered how she thought about the marchers during class. Were they poor, too? she asked herself. Did they think about helping their families? Had they been hungry? Did they dream of going to college? Did they want a better life for their kids? Retreating to the school rest room, Martina devoured the protest leaflet featuring a shackled man on the cover. It turned out that the marchers represented the Communist Party. When I first realized there was a socialist world that believed in working people equality I was very excited, she later recalled. The leaflet was direct and to the point. It gave me hope. The impoverished art student felt as if she were slipping into a brave new world. Socialism converted my dreams into a science, a reality, she subsequently explained. Nevertheless, Martina found herself depressed, discouraged, and exhausted at the end of four years of art school (she never graduated) and retreated to the sparse five-acre Tualatin spread where her mother and son lived. This was the winter of hibernation, she explained in subsequent notebook entries. I slept all night and most of the day. It was not until June 1936 that she felt well enough to return for work in the cherry orchards. Two events occurred in the momentous year after Martina left art school. First, she joined the Communist Party, a natural outgrowth of the social activities she had participated in at the Young Communist League. Beginning in 1935, Party leaders and prominent fellow travelers in the literary community encouraged the development of the Popular Front, a broad anti-fascist coalition emphasizing humanist and democratic values like world peace, labor solidarity, racial tolerance, and liberal reform. In matters of culture, the Front celebrated the dignity and beauty of proletarian art forms while offering support to working-class ethnics and blacks hoping to become visual or literary artists. Frustrated at the slim prospects for making a living in the vocation she loved, Martina aligned herself with the communists because she hoped that socialism could turn her dreams of a better society into practical reality. People joined the Party because of their immediate problems food, shelter, etc., she later commented. Since she had gone to art school, Gangle was placed in a club of intellectuals and artists. Once again, she was uncomfortable in what must have been a strange setting. The leader of the branch, she recalled many years later, was an anemic looking Reed College graduate. I didnt understand a word he said, Martina remembered. College talk went past me. The long speeches of male comrades also bored her. But having worked for bosses, she once explained, I felt I understood how much being able to have their say did for them so I listened to a lot of fifteen-to-twenty minute introductions with patience. During 1936 Martina also applied for a position with the Federal Arts Project, the New Deals ambitious effort to support visual artists, writers, and dramatists under the auspices of the massive Works Progress Administration (WPA). With no prospects for gainful employment and her mother unable to pay her property taxes, Gangle went to Portland to apply for relief to qualify for a WPA job. Resenting the fact that the Reed College student caseworkers treated artists as if they were fortunate to get a handout, Martina nevertheless welcomed the $90 a month stipend. She and David lived with an art school friend named Betty in an apartment halfway up the West Hills above the Goose Hollow neighborhood. The three supplemented their meals with fresh vegetables from the Gangle family garden in Tualatin. Yet the young artist remembered feeling uncomfortable with her roommates middle-class friends who had none of the tribulations she had known. When Betty got pregnant and then married, Martina found a $10-a-month studio apartment on S.W. Montgomery Street with an eight-by-nine-foot bedroom and a long, cramped kitchen with a gas stove and a narrow bed for David. Martinas first assignment was to paint watercolors of wildflowers and ferns to decorate the rooms at Timberline Lodge, the ambitious new WPA ski lodge and tourist facility being built on Oregons Mt. Hood. With little experience in watercolors, she struggled with the medium but received help from a woman colleague. In the end, she completed several paintings of trilliums, huckleberries, and tree leaves that she half-liked. Over the next three years Martina added to Timberlines permanent public art collection with several woodcut engravings, a linoleum block entitled WPA Workshop, and a wood carving of cherry pickers. Three of the engravings were included in The Builders of Timberline Lodge, a book published by the WPA in 1937. In the late-1930s Gangle merged art with progressive political consciousness. After spending a brief period as a teacher in the Portland Public Schools art adult education program, she focused on her own work. In 1937 a Gangle block-print entitled Fruit Tramps was included in the Portland exhibition of the radical American Artists Congress. County Hospital a stark linoleum cut of poor women, blacks, and children patiently waiting for emergency care was accepted for the 1939 New York Worlds Fair collection of American art. An oil painting entitled Workers Alliance Conference was shown at the Portland Art Museum in 1940. Martina also had entries in the 1939 and 1940 Northwest Printmakers Exhibition in Seattle. Her memorable linocuts, lithographs, and etchings often portrayed migrant worker camps, Timberline artisans, African Americans, women, and poor children. Once the WPA ceded direct management of the arts program to the states in 1939, Gangle signed on with the Oregon Art Project (OAP). Her most ambitious task involved two murals in tempera commissioned for Portlands Rose City Park Elementary School. The Columbia River Pioneer Migration (1940), in the artists own words, illustrated family, the Indians, and the white people getting together. For nine months Martina worked in the school basement to produce a panel showing pioneers crossing the Columbia on a raft as a woman is saved from drowning. When she was scolded by the principal for coming in late while doing research for the project, she retreated to her downtown studio to complete the second panel, a task that took another nine months. |

|||||

| Gangles second mural project involved Arthur and Albert Runquist, two older artists she had befriended through the communist movement. As she recalled for her sister in the late-1980s, the Runquist brothers took me under their wings and educated me about life in general and helped me with my art work. |

|

||||

| As

a self-described sister, Martina agreed to assist the brothers on

Early Oregon (1941), an idealized OAP mural for Pendleton High School

that featured western Indians and cattle drivers in peaceful harmony. Her two panels depicted the everyday life of settlers, including a portrait of a boy with a banjo that resembled her son David. Despite the non-political tenor of the work, Martina maintained that Arthurs radical politics led to his abduction while walking off a drunk one evening in Portland. Taken to a park, beaten, and left bleeding, Runquist wound up with an infected hand that hospitalized him for months. The association with the Runquists helped to politicize the impressionable young artist. Thriving on camaraderie with other WPA jobholders, Gangle became treasurer of the Oregon branch of the Union of Cultural Workers, helping to affiliate the local with the new Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). She worked with progressive artists on sign making for the union as well as a CIO float for Portlands Rose Festival Parade. Joining the Oregon Arts Guild, Martina also became secretary of the radical Workers Alliance of Oregon. In this capacity she organized support for the anti-fascist loyalists in the Spanish Civil War and attended a national unemployment conference. As a Communist, Gangle pushed for the League of Nations to stop Nazi Germany and its allies from growing stronger and engaged in pamphleteering and demonstrations to encourage boycotts of aggressor nations. She was even arrested with two sister comrades for picketing a Japanese training ship in Portland in 1938. |

|||||

|

Martina believed that she paid dearly for her radical activities. On one occasion she remembered being summoned to the FBIs Portland office where she was told that the agents would see to it that she never became a successful artist. Gangle also claimed that the police told a young male friend of hers that she was a chippy, presumably because out-of-town loggers and progressives like Hank Curl often stayed overnight at her place. Martina further recalled that a man once asked her to lunch as she sat on a downtown park bench, an invitation she declined for fear of being set-up for a prostitution charge. | ||||

Such harassment was difficult for the former migrant worker to comprehend. Her Depression radicalism, she always insisted, came from frustration and humiliation...and also anger, when I saw the wasted food in fields and learned that pigs were ploughed under and fruit rotted in piles guarded from hungry people. For Gangle, the communist movement was about working for social security, good labor laws, solid unions. Party members, she reminisced in later life, worked to get these necessities for people who were actually starving and homeless by sit-downs, demonstrations, etc. She took pride in pointing out that the Workers Alliance staged occupations at welfare offices to get help for Dust Bowl migrants and others in need. Martina always had a problematic relationship with arts project administrators, whom she suspected of condescending and exploitative attitudes toward working-class artists. She claimed to have been fired twice by the same WPA supervisor and of losing eligibility for the program anytime she saved any money. On one occasion she told David that if another depression came shed prefer to live in the Hooverville shacks of Sullivans Gulch (presently the roadbed of the Banfield Freeway 1-84) than go through the rigmarole of getting on relief again. The demise of WPA funding in 1942 may not have been the worst prospect for Martina Gangle. After returning to strawberry picking with her family that spring, she signed up as a welder for the Kaiser Shipyards in Vancouver, Washington. By now the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union were allied in a peoples war against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan and three Portland-area shipyards were prime suppliers of the nations seaborne arsenal. Martina worked swing and graveyard shifts in the noisy and smoky yard but also did some blueprint drafting and other illustrations. In spare time, she sketched pencil drawings like Welding Double Bottoms and Shrinker Applying Water and Flame to Level Bulges in Deck C. Intimate watercolors, gouache portraits, linocuts, and lithographs depicted scenes ranging from the womens locker room to the welding process and every aspect of shipbuilding. One memorable watercolor pictured workers on cigarette break under a No Smoking sign. A gouache piece reproduced a temporary graffiti on a ships undercoating warning about a supervisor known as Walt the Wolf. Like many women workers in the defense plants, Martina was abruptly laid off as war orders tapered off in the spring of 1945. Fully committed to the struggle against fascism, she signed up for the Waves but was rejected because of bad teeth. Finding herself exhausted from shipyard work, Gangle managed to get on unemployment and receive $82 a month. By the time Japan surrendered in the fall she had resumed her artwork and found a circle of friends at a downtown watering hole known as the Brass Duck. As her savings evaporated, however, Martina returned to picking beans, cucumbers, strawberries, cherries, and other crops on Sauvie Island northwest of Portland and in The Dalles in the Columbia Gorge. In 1946 she married Hank Curl, a former logger and politically oriented Merchant Marine carpenter she had known since the mid-thirties. Fruit orchards near The Dalles were an inspiration for Martinas watercolor and gouache paintings of the life of camp women and children, which she depicted as strong and self-reliant figures. Critics have noted how elements of fantasy in this work predated the earth mother motifs of the 1960s. Gangle embodied similar themes in the lithographs and linoleum and wood block prints she showed at the 4th Annual Oregon Art Guild Exhibition in 1948. Meanwhile, she returned to Communist organizing. With a postwar recession on, she later explained, Party activities were lively, particularly with shipyard labor activists and blacks staying in the area after V-J Day. Martina was elected chair of her branch in 1948, the first time, she once recalled, that she ever had any kind of leadership. Yet she quickly ran into difficulties with a district organizer who expected her to dress up when arranging a room for an official function at a downtown hotel. Phooey on you, she remembered thinking. I had never worn or wanted high heels and I had a 24-inch head and couldnt get a decent hat unless I paid more than I could afford. When it rained that day, Martina defiantly dressed in her overalls and customary scarf. |

|||||

| Martinas iconoclastic approach to Party discipline reflected a distinct worldview that found poverty and suffering to be absolutely intolerable amidst plenty. We have got to learn to respect the Laws of Nature, she wrote in one of her frequently rehearsed notebook entries. We have yet to apply the Golden Rule to all People of the World. We have yet to admit that greed, with its resulting poverty and insecurity, is destroying our young. |  MGC-Nurture (lithograph) |

||||

| An excerpt from Ecclesiastes, found in Martinas papers of the late-1950s, captures the essence of her politics: There is nothing better than people should rejoice in their own works.... Moreover, the profit of the earth is for all.

In short, Martina Gangle believed in the Golden Rule: people were to

deal with others the way they would like to be treated. She supported

the communist program, she once wrote, because it addressed equality

and justice, jobs, and unity with all working people. In a letter to a granddaughter in the early 1970s, Martina explained her commitment to the communist ideal. She traced her basic ideas of right and wrong as well as the ability to think for herself to her mother. What sustained her, she wrote, was the sprouting of seeds after many small changes, the sudden change in people after years of oppression, the change of individuals after years of hard experiences almost overnight. Nevertheless, Martinas fierce independence of mind what she called her hard-headed spirit resulted in her expulsion from the Communist Party between 1953 and 1961 when she took the initiative in criticizing the dictatorial style of the District Organizer. Those were very bad years for us, she recalled in a personal history written for a Party meeting in the late-1980s, since rank-and-file members up and down the coast were told we were enemies of the working class and the FBI did what they could to keep us very poor.... Living on SW Bancroft Street, Martina found work with the Methodist Federation for Social Issues for some $600 a year. Bitterly opposed to the McCarran-Walter Immigration Act of 1952, which legalized the deportation of foreign-born U.S. citizens accused of Communist affiliations, she became secretary of the Oregon Committee for Protection of the Foreign Born and secretary of the Mackay-Mackie Defense Committee. Activism on the immigration front prompted correspondence with hundreds of people across the world and the amassing of thousands of signatures on protest petitions. Martina also helped to gather support for the Stockholm Peace Petition for nuclear disarmament. When the state bought the Bancroft Street residence to make way for the I-5 freeway in the early 1960s, Martina and Hank moved to rural Sherwood and then to Tualatin. Setting up a studio in the country house, Gangle returned to her artwork, painting trilliums and other flowers from her garden as well as several watercolor portraits of her prize rooster and chickens. If I were a choreographer/Id do a rooster dance for sure, she exclaimed in a poem. Another verse described a peaceful cat sleeping on her lap. Continuing to struggle around peace and human rights issues, Gangle traveled to Washington, D.C. in August 1963 to march for civil rights with Martin Luther King, Jr. and 250,000 other protesters. |

|||||

Friends Julia Ruutilla & Martina sleep-in at PP&L 1975 |

When in 1971 both Arthur and Albert Runquist died in the house on N.E. Clackamas Street that Harry Wentz had left them, Martina helped sort out their personal belongings. To her dismay she learned that the artists surviving sister intended to dispose of all their paintings in the trash. It was only when Martina pleaded that the collection be turned over to people who knew about art that the Runquist heir realized its monetary value and assumed control of the work. | ||||

The Curls then purchased the house and used it as a rental until moving in themselves in 1989. Meanwhile, Martina kept custody of the invaluable Runquist paintings of the shipyards and North Oregon Coast that had been gifts to her by the artists. As the nation sank into a renewed economic recession in the mid-1970s, Martina joined labor activist and friend Julia Ruuttila in a widely publicized sleep-in against rate increases imposed by the privately owned Portland Power and Light Company. After a brief stint behind bars, the charges were quickly dropped. Joining the Coalition for Safe Power, whose monthly meetings were held at the Centenary Wilbur Methodist Church in Southeast Portland, Martina submitted to another arrest in 1977 as part of a nonviolent protest at the Trojan Nuclear Power Plant in Rainier, Oregon. Meanwhile, she and Hank Curl had become active in the Farm Workers Boycott Committee, a support group for labor activist Cesar Chavezs union of Mexican American migrant laborers. We learned that many of the dedicated people we worked with, Martina explained in a later notebook entry, lacked a good knowledge of history, especially on the struggle to organize labor and the socialist countries. The experience prompted the couple to start the John Reed Bookstore, named after the Portland native son, author of Ten Days That Shook the World (1919), the most influential account of the 1917 revolution creating the Soviet Union. Martina raked filberts to raise the $1,200 needed to start the business, which opened on the sixth floor of the downtown Dekum Building. Moving to street level on S.E. Hawthorne in 1987, the store served as a unique center of radical and working-class literature until it closed four years later. During the early 1970s the Curls agreed to go out to the public schools to present talks on their experiences in the Great Depression, the labor movement, and the peace and social justice movements of the 1950s and after. To prepare for these ventures in public speaking, Martina filled her notebooks with longhand versions of each presentation literally dozens of copies of the same speech survive in her papers. Yet by the end of the decade, new Party leaders paid little attention to the older veterans of the movement, considering her an old fogy behind the times, Gangle once observed. I have never thought of myself as being a leader, Martina reflected in her personal history, but I do believe I can see things that others sometimes cant so I let people know. And almost always I am rightmy name should be Cassandra, the prophetess that no one believed. During the 1980s the Curls opposed military assistance to repressive El Salvador, objected to aid to the Nicaraguan contras, and supported the nuclear freeze movement and other campaigns against atomic weaponry. The couple continued to distribute the Communist newspaper, Peoples World, each week to workers at the gates to Portlands Swan Island shipyards. They call me mother and give me nice smiles, Martina wrote her granddaughter in 1992. I especially appreciate the smiles. They give me energy to stay on my wobbly feet. On February 20, 1994, Martina Gangle Curl died at the age of eighty-eight. Survived by her husband, her remaining siblings included her sister Tillie and brother Lawrence, both of whom lived on the coast in Waldport. The family requested that remembrances be sent to PCUN the Mexican American farm worker union headquartered in Woodburn, Oregon. Martina Gangle was a uniquely endowed class-conscious artist who portrayed the life and labor of working people with imagination, compassion, and wit. Her paintings, drawings, and block prints were infused with a celebration of ordinary existence that nevertheless dramatized the social injustices she saw under capitalism. For Gangle, art offered a way of criticizing the present while pointing to a desired future. Her work falls within the genre of democratic realism an embodiment of nationalism, regionalism, and socialism rooted in the progressive cultural front and public, participatory art forms of the 1930s and 40s. Fascinated by migrant labor families and shipyard workers, she expressed a profound understanding of the universal dignity of all people. Her particular attention to women and children conveyed a religiously inspired desire to mother humanity. Following such impulses with complete honesty, Martina Gangle succeeded in dramatizing the beauty and aesthetic diversity to be found in the everyday settings and people of the Pacific Northwest. |

|||||

Sources

Allen, Ginny and Jody Klevit, Oregon Painters: The First Hundred Years (1859-1959). Oregon Historical Society Press, 1999.

The Builders of Timberline Lodge. Works Progress Administration, 1937.

Colman, Roger, Oregon Artists Source Book Circa 1941. Portland State University, 1979.

Connor, Michael Ames, The Simplest Thing / So Hard to Achieve: American Communism Remembered. Reed College B.A. Thesis, 1990.

Del French, Chauncey, Waging War on the Home Front: An Illustrated Memoir of World War II. Oregon State University Press & OCHC, 2004.

Filips, Janet, Hard Times for Big Dreams, Oregonian, April 3, 1992.

Gragg, Randy, Art and Real Life, Oregonian, September 29, 1996. ___________, The Womens View, Oregonian, March 28, 1997. ___________, The Workers and the War Effort, Oregonian, September 26, 1999.

Griffin, Rachael, Art of the Pacific Northwest from the Thirties to the Present. National Collection of Fine Arts for the Smithsonian Institution, 1974.

Hayakawa, Alan R., Influential Art School Celebrates 75 Years, Oregonian, October 3, 1984.

Howe, Carolyn, The Production of Culture on the Oregon Federal Art Projects of the Works Progress Administration. Portland State University M.A. Thesis, 1980.

Kovinick, Phil and Marian Yoshiki-Kovinick, An Encyclopedia of Women Artists of the American West. University of Texas Press, 1998.

Martina Gangle Curl, Oregonian, February 24, 1994.

Polishuk, Sandy, Sticking to the Union: An Oral History of the Life and Times of Julia Ruuttila. Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Reed, John, Ten Days That Shook The World. Boni & Liveright, 1919.

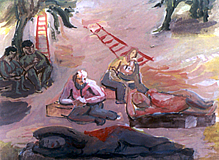

MGC Orchard Rest (gouache)

MGC Orchard Rest (gouache)